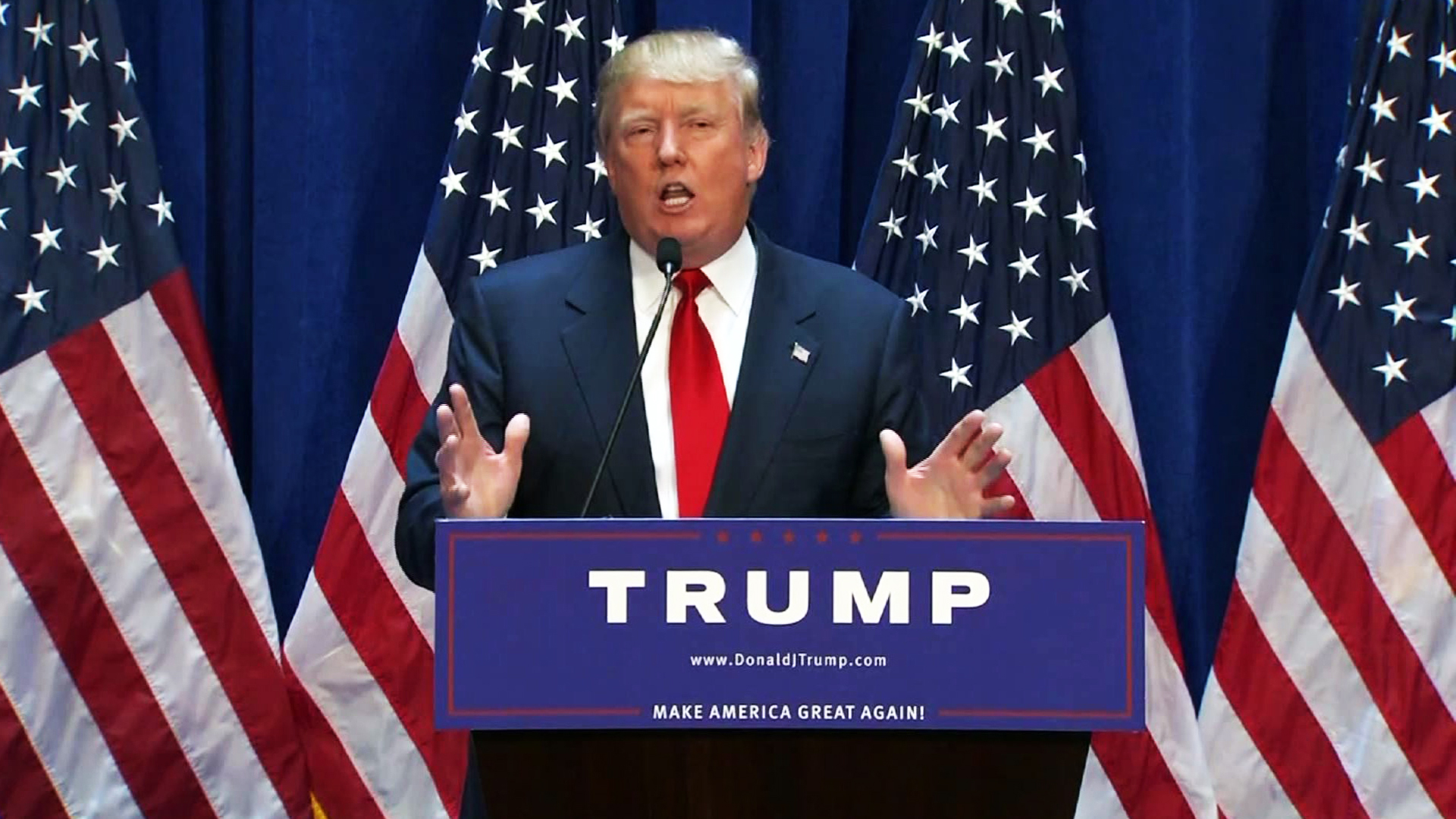

The attacks in Paris and San Bernardino have brought immigration and refugee policy to the front of politics, charging discourse with fear and outrage. Earlier this week, Donald Trump’s campaign proposed a new immigration plan that would enforce a "total and complete shutdown" of the entry of Muslims to the United States. The Republican presidential candidate supported his statement by mis-referencing a small Pew poll that shows that Muslims in America display a great amount of hatred towards the United States. He went on to claim, “Without looking at the various polling data, it is obvious to anybody the hatred is beyond comprehension.”

The proposal received immediate condemnation from commentators on the left and right, both for its lack of credibility (The Onion tweeted one of its old headlines in response: “Man Already Knows Everything He Needs To Know About Muslims”) and the logistical impossibility of banning Muslims from the US.

Part of me wants to look the other way and not bother with Trump’s statement. It is so offensive it is ridiculous, not the worthy subject of a national discourse. On the other hand, it may be a harbinger of a wider conversation regarding religious liberty that I think merits serious attention.

Moments like these throughout history have warranted taking a step back and one deep breath before allowing phobia to shape policy. In his press conference with French President Francois Hollande on November 24, President Obama captured this: “There have been times in our history, in moments of fear, when we have failed to uphold our highest ideals, and it has been to our lasting regret.” Freedom of religion sits somewhere near top of America’s list of “highest ideals,” and how we uphold it at home largely shapes how we do so abroad (the New York Resolution for Freedom of Religion or Belief, signed by an international panel in 2015, is a good read on this). Let us not begin to participate in the kinds of narrow-mindedness toward religious outsiders that is the source of so much suffering we witness.

We easily forget that protecting religious liberty is an active job, not a passive tolerance. That freedom requires providing equal protection under the law to every individual, but it also means empowering religious communities of all kinds to provide services and to uplift cultural and economic freedom as well. This is impossible in a climate of Islamophobia—and if you don’t believe that mood is growing, do some browsing on Twitter. Engy Abdelkader, who serves on the US State Department Religion and Foreign Policy Working Group, put it simply: “American Muslims can’t go it alone.” If we pursue freedom for persecuted Yezidis and Christians, we’ll have to uphold the same rights within our borders—especially in seasons of fear.

My aim is not to propose the right policy here, nor to disregard an emotional reaction to the tragedies of the past month. Addressing security concerns alongside human rights is important and not easily done. But as you think about the conversation surrounding the refugee crisis and immigration, I urge you to fight against any tendency towards phobia. Instead, cherish the freedoms you have and the radical, challenging work that goes into upholding them. Desire it for those from whom it has been taken.