On Sept. 25, British dance-pop duo Disclosure released their sophomore album, Caracal, in standard 11-track and “deluxe” 14-track formats on CD, digital download, Spotify, and even vinyl.

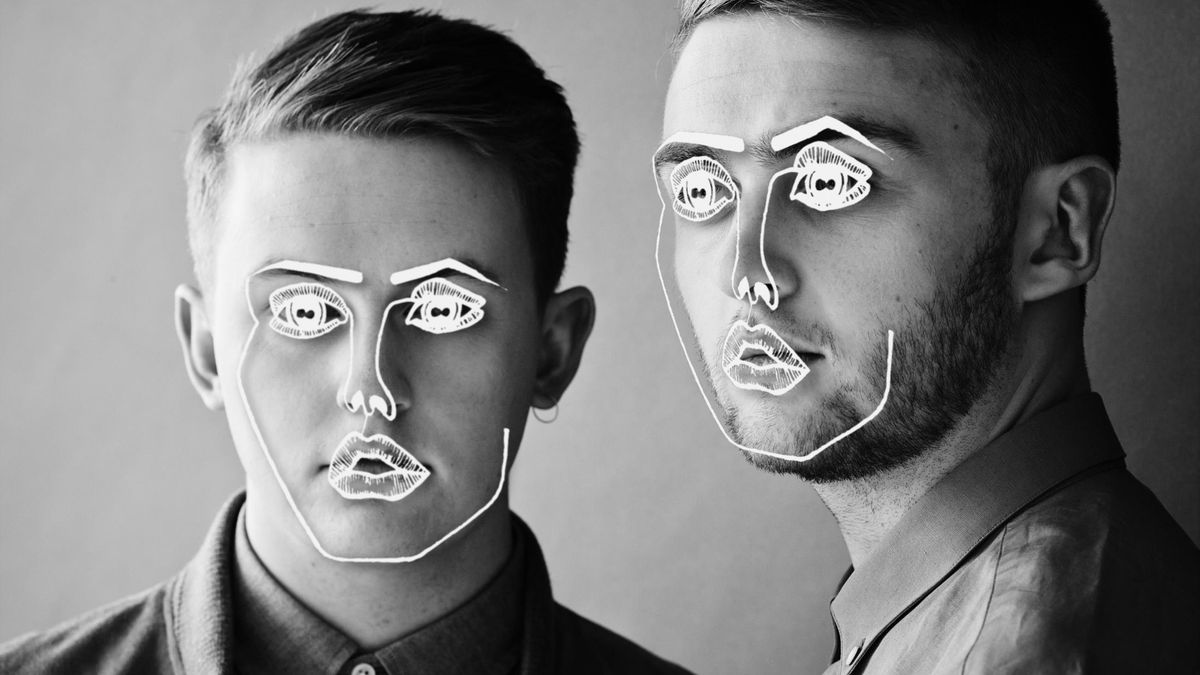

UK brothers Howard and Guy Lawrence rose to dance music fame in 2013 with their first album Settle. Sporting the hit single “Latch” featuring Sam Spade, as well as other successful collaborations with Mary J. Blige, Eliza Doolittle and others, the album topped both UK and US charts soon after its release. Critically, Settle was heralded as a breakthrough for both the Lawrence brothers and the dance-electronic genre.

Critic Michaelangelo Matos echoed the general consensus, saying, “Settle was a genuine line in the sand, one that helped move the new rave generation away from EDM’s blunt blare and toward quicker, slicker and subtler beats.”

Like Settle, Caracal intentionally shifts away from the established sound. In a July interview for the LA Times, Guy admitted that “[EDM] is everywhere now ...the same old bass lines, the same old samples. We're a bit bored with it… I want people to hear this record and think, 'Wow, they can do more than just a jacking house beat.'”

However, the established sound is Settle, meaning that Caracal now moves away even from what is expected of Disclosure. The former album’s club-wall-pounding beats and intense Latchy lyrics are supplanted with something even “slicker and subtler” in the latter, resulting in a mix of slower tempos, heavier lyrical emphasis, and an intended slant towards a more pop/R&B sound.

Caracal takes its thematic cues from a particularly striking African wildcat of the same name, known for its solitary habits and skilled nocturnal hunting. From these attributes all the way down to the shadowy cover art, the symbol fairly well reflects the album’s major themes.

For starters, Caracal is decidedly nocturnal, and establishes a strong atmosphere of the night life in every track. Appropriately, the track “Nocturnal” opens up the album by diving straight into nightfall with “Streetlights turn on one by one / My hope... descending like the sun.” From here the listener is ushered directly through the neon lights and dusky front doors of the underground clubs, where bonus track “Bang That” rings as the crass, repetitive stand-in for entry level club-fare.

“Magnets,” aided by a sauntering syncopation and “half-shut eyes,” calls up more potent dancefloor sensuality with “Uh-oh, dancing past the point of no return.” “Molecules” echoes from the male perspective: “I’m attracted by the way that you move” and “These lights are too bright / let’s turn them down…” “Hourglass” treats the “sunlight as a warning,” and, like “Magnets,” dons the huntress persona for the night while it lasts.

Even as it establishes the night life, Caracal isn’t satisfied with cheap thrills, hungry for something more substantial. Tracks like “Nocturnal” and “Moving Mountains” outweigh shallow desires with mournful notes of hopelessness and fatigue: “Why can’t I find peace, when a caracal could sleep tonight?”

Sentiments of despair over love and ensuing loneliness haunt other tracks. The speaker is at best grasping at some kind of love -- as in “Willing & Able” and “Masterpiece” -- but more often finds himself trying to let go of bad love, as in “Holding On” and “Echoes.” Worse, some relationships are already long-gone, often ruined by his own hands (see “Omen,” as well as “Good Intentions” and “Afterthought”).

Aside from this, some of Caracal’s tracks strike a decidedly critical tone, perhaps of the unnamed speaker or of the night life itself. “Jaded” weighs heavily on the theme with accusations of insincerity -- “Take a look at yourself and the stories you tell / Does the truth weigh on your mind?” -- as does “Echoes.” “Superego” is softer but still takes a stern, friend-to-friend approach to calling out pride: “So you better hold it… down / Where’s your superego?”

Thematically then, Caracal dwells entirely in the night, as though by nature and habit, but it reveals a desire for something more. It has wandered in and out of neon lights and lovers like clubs on Mulholland, and carries all the scars to prove it.

It is worn out by shallow pursuits, haunted by remorse from broken relationships. And it is aware of a pervasive insincerity in its surroundings -- even the pride within itself, though it tends to externalize. But through all of this, still it searches on for some semblance of authenticity in love and in life, some glimmer of daylight beyond the darkness.

As far as sound is concerned, Caracal delivers. Well-chosen pairings with Sam Smith, the Weeknd, Miguel, and Lorde add their own qualities to Disclosure’s lyrics. Less well-known artists like LION BABE, Nao, and Jordan Rakei fare similarly well, and even Disclosure brother Howard Lawrence steps up to the mic with relative success. Catchy hooks and slick R&B chord progressions set the groove well and beckon any dance party worth its bass to take them on.

More important than the aural experience in this reviewer’s humble opinion, however, is the thematic atmosphere Caracal establishes, and the revealing comments on that atmosphere it makes along the way. Since the reader is likely to hear these tracks in the near future, I recommend giving some thought to what’s being said within.

Listeners may take Caracal’s wearied, remorseful overtones as mere melodrama, but perhaps it is Disclosure’s genuine comment on their most typical cultural scene: The night life may seem fun, but there’s more darkness here than good, and what we’re really looking for ultimately can’t be found here.